BATTING FOR BEGINNERS: IDENTIFYING AND TRACKING LOCAL BATS

by Doug Pifer

Last month I got a bat voice meter that attaches to my cell phone. With a touch of my finger I can now record the sound of any  bat within range. It even tells me which species of bat I’m hearing. That little gadget has introduced me to an unseen world of nature at night.

bat within range. It even tells me which species of bat I’m hearing. That little gadget has introduced me to an unseen world of nature at night.

For a long time, scientist have known that bats, shrews, dolphins, and certain birds can navigate, forage, and communicate in the dark by emitting sound waves beyond the threshold of human hearing. Special structures within their delicately tuned ears enable these creatures to conduct their lives in total darkness by capturing their own sounds bounced off objects.

Over the last decade, scientists have developed sophisticated detectors that pick up the ultrasonic calls’ bats make, erase other sounds, and record bat calls as spectograms. Spectograms can be used to identify which species of bat is making the sound. Using specialized equipment, the recordings can be slowed down in several ways, so they are audible to the human ear.

Since bat-detecting technology has become more available and user-friendly, people have become interested in finding bats as a hobby. “Batting” can now be as fun and interesting as birding.

HOW DOES IT WORK?

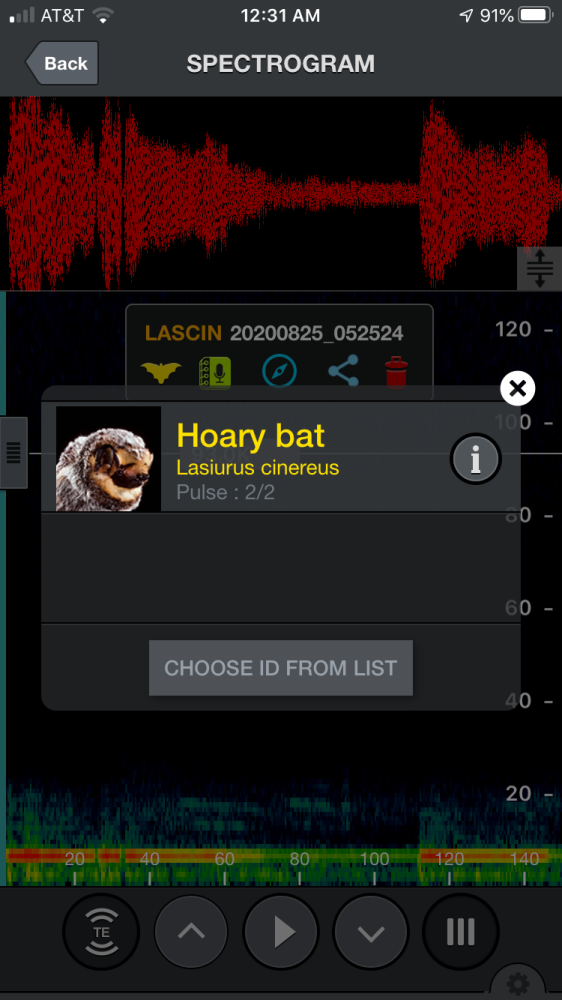

My Echo Meter Touch 2 for IOS plugs into the lightning port of my iPhone. Then, using the dedicated app, I can push a button and instantly start detecting bats. When a spectrogram is displayed on my phone screen, I press another button and the device immediately records and slows down the bat sound so I can  hear it in real time.

hear it in real time.

As I record, auto I.D. automatically selects which bat I hear from a list of species occurring in West Virginia. It cannot identify every sound a bat makes. Sometimes it offers two possibilities, the first choice being the species it is most likely to be. A “mug shot” photo of each species can also be displayed, with a link to Wikipedia for more information.

Best of all, each recording has a GPS location. A satellite map using Google Earth displays the flight path of each bat, color coded by date, showing exactly where and when each recorded bat flew over our property.

FASCINATING DISCOVERIES

Since late August we’ve recorded between seven and nine species of bats flying over our 5.7-acre property. The list includes big brown bat, eastern red bat, hoary bat, silver-haired bat, little brown bat, evening bat, and tricolored bat. Two “possible” second-choice species complete the list, the Indiana bat and Townsend’s big-eared bat. The endangered Indiana bat is much like the little brown. Townsend’s big-eared bat is found only in parts of Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky. Its jackrabbit-like, naked ears fold back like accordions when the bat roosts in caves, old buildings, and abandoned mines. Called a “whisper bat,” its sounds are seldom picked up by bat detectors.

Interestingly, our most recorded bat is the hoary bat, the largest species in West Virginia. I’ve never seen a live hoary bat, but evidently, they often fly to and from a big arborvitae tree about 40 feet from our front porch and may roost there. Our next most oft-recorded species are the big brown, silver haired and red bats. Little brown bats, once abundant, have been decimated by a fungal disease called white nose syndrome. We feel lucky to have them here! ###